This was a guided group with four people on the slope at the same time. These four people were caught in the slide and carried downhill and only partially buried. Other than some gear being lost, no injuries were reported, and everyone involved made it out safely.

At the bottom of this report we have posted the comments submitted by the lead guide.

Much of the adjacent terrain that is less steep was covered in ski tracks.

Periodic storms during October, November, and early December interspersed by long durations of high pressure allowed the snowpack to develop weak, faceted layers of sugary snow. Storms accompanied by west/northwest winds from Saturday 12/23 through Monday 12/25 deposited 2' of storm and wind-drifted snow in upper Little Cottonwood Canyon, overloading these buried weak layers.

Date Wind Water 12/22 Northwest avg: 20 mph gusts: 42 mph 0.35" 12/23 West avg: 24 mph gusts: 53 mph 0.6" 12/24West avg: 18 mph gusts: 42 mph

0.9" 12/25 Northwest avg: 16 mph gusts: 48 mph 0.15"It is likely the west/northwest winds on 12/22 and 12/23 created the 4" 1F slab on top of the faceted layer where the failure occurred.

Avalanche activity on mid and upper elevation slopes facing north through east, and continued reports of collapsing and cracking, throughout the week prior to this incident indicated continued instability.

This was a classic persistent slab avalanche:

1. There were numerous tracks on adjacent slopes with no evidence of avalanching;

2. The fourth skier on the slope triggered the avalanche.

With a persistent (or deep) avalanche problem, tracks on a slope are zero indication of stability. All it takes is for one person to find a weak spot and the entire slope can avalanche, taking out prior tracks. These types of avalanches also allow a rider to get well out onto a slope before avalanching, and it is not uncommon for the avalanche to fracture widely - and above the rider.

From reports we have received, more than one skier was on the slope when it avalanched. It is crucial to only expose one person at a time on a slope, and get out of the runout zone at the bottom, and then wait for the next rider to enter the slope.

Our current persistent slab structure can easily be identified by digging down 1 to 3' deeply in the snowpack. If you find the structure of strong snow (denser, harder to penetrate) over weak snow (softer, easier to penetrate) this is evidence of a poor snowpack structure, and the types of slopes that should be avoided. In the Wasatch mountains, this problem currently exists on mid and upper elevation slopes facing north through east.

Below are the comments submitted by the lead guide:

Dry Fork Avalanche...Contributing Factors/Accident debrief

On Friday, 12/29/17, around 10:30-11 am, there was an avalanche accident involving 3 clients, while I was leading a group of 8 guests with another established guide and one aspirant guide.

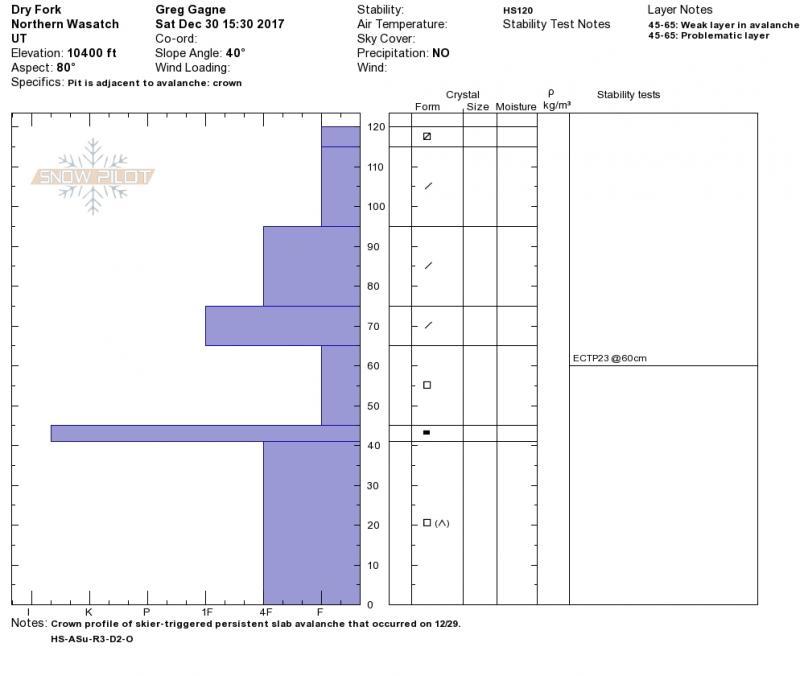

We decided to ski an east-facing slope of about 35 degrees: the middle entrance to Dry Fork from Alta. This slope had been skied over the previous few days without incident. I dug a hand- pit down to the facet layer and it was not reactive.

The 10 sets of tracks and an up-track on the middle entrance proper pushed me to find a cleaner line for my clients. I was lured right by untracked snow, and decided to open up slightly steeper adjacent terrain. I ski cut about 120 feet south and then skied fall-line for 250 feet, and back north to an island of safety at the bottom of the short pitch.

Although the snowpack was unreactive to my ski cut and run, I did feel some apprehension. However, I thought the run could be safely skied by individual skiers going one at a time.

The second guide, perhaps thinking he needed to be lower on the slope to keep an eye on clients as they skied further right, made a few turns on the slope to a tree. The first client then followed my traverse, and the 2nd client followed just 20 feet behind him. Then, as I watched in horror from below, 3rd client followed onto the starting zone, another 30 feet behind.

Before any of them had actually turned down the fall-line, 3 were on the traverse and it fractured about 100 wide and 2.5 feet deep, pretty much connecting the dots between them. Crown was just above the clients. All 3 were carried 100 - 200 feet. Two lost skis, but all 3 stopped without injury. Two were partially buried, but dug themselves out. One ski was not recovered.

Human Factors:

This was a party of 11 people. We intended to split the party at the bottom of this first pitch of skiing, but we were all together to start. Communication somehow broke down and three people skied at once.

Due to low snowpack, most safe slopes in the upper Cottonwoods had already been skied by multiple parties. My decisions were affected by scarcity.

My previous guiding days in this early season had been avalanche training, where there was no reason to be on steeper terrain. These experienced, enthusiastic clients were back for their 4th season with me, and I was eager to get them out of the tracks on Point Supreme and give them some decent powder.

Second guide and I agreed on a plan “A” to ski the middle entrance to Dry Fork, but I changed to plan A+ by opening up the terrain to skier’s right.

Weather:

We skied at 10:30-11 am, on an East aspect, and it was a warm, sunny day..

Terrain:

This slope was 40 degrees with some rocks in bed surface. Middle entrance proper was 35.